By Ruth Tindugan, ablethroughlife@gmail.com

What sounded like the screams of a duckling pulled me out of the deep pond of sleep. At one o’clock in the morning, Arne was yelling again. I nudged my husband, but he did not budge. Most of the time, I would stagger into his bedroom and check on him. My toes stirred reluctantly while my body remained glued on the bed. But at the next yell, a hot wave ignited from my belly, rushed through my chest and on to my temples. I bolted out of bed, and burst into Arne’s bedroom. Like a dragon, the heat inside my head shot out of my mouth. “You are going to walk, Arne! Do you hear? You are going to walk!” I pulled him out of bed from his armpits, turned him around, and placed his legs and feet on top of mine. I held him tightly around his

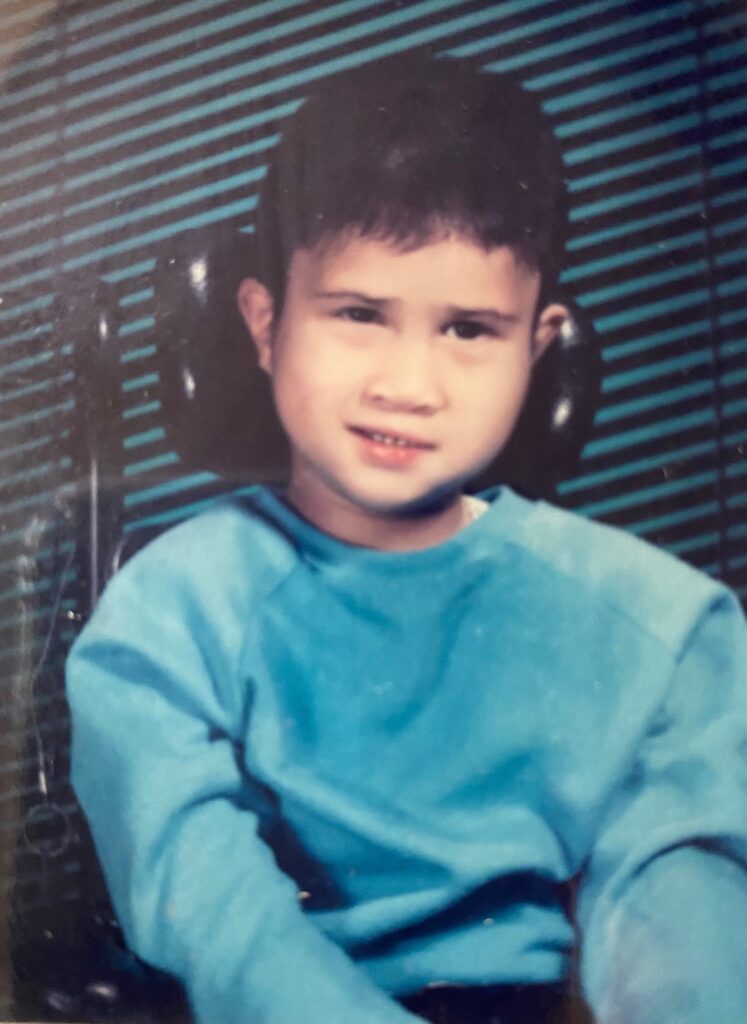

chest, and with the back of his head touching my navel, I started walking. Down the hall, past the living room, around the dining table, and back again. He moaned and wailed as each step stretched his stiff thighs and legs. I kept walking. At five years old, he was incapable of resistance.

When he was ten months old, we took him to see the neurologist at the Children’s Hospital after he’d had some tests. A quick glance at the doctor’s diploma mounted on the wall informed me he had just completed his residency. He greeted me with a solemn look on his face.“I spent more than an hour with the MRI doctor discussing your son’s condition,” he said. He pointed to an open thick book on his desk. “There is a short paragraph in this book about delayed myelination,” he continued. “And, honestly, I don’t know much about it.” He fell silent. I wanted to ask, What is delayed myelination? Why is he having seizures? And other questions hovering on my mind like tiny winged insects fluttering over a slush of the murky unknown. But I sat there mute as a stone for I felt it was useless to ask him anything since he himself was looking for answers. He closed the book and said softly, “Your son will need a lot of care.” I offered a silent wish on his behalf—may your research and experience increase. On my way out, I asked

the receptionist for a referral to UCSF Medical Center.

A few weeks later, my husband and I were at the office of the head of Pediatrics Neurology. Prior to the appointment, the neurologist had called to bring Arne so he could observe him. I bundled my son in a white and red polka dot baby sack. Its hood partly covered his head that revealed a tuff of black, straight hair, shooting upward like a porcupine. The neurologist was an older man, tall and lean. He read Arne’s referral notes with an occasional glance at the stroller where Arne was fast asleep. In the silence, fragments of memories came to mind. I remembered the low feeling of joyless surprise the moment I knew I was pregnant again. I coined my grandparents’ names—Arsenio and Nenita—and named him Arne. I recalled the warmth of this newborn’s body—6.5 pounds and 19 inches— as he was laid between my thighs while the nurse cut the umbilical cord that tied us together for thirty-seven weeks, and I remembered wondering why Arne’s first cry was not as shrill and piercing as his older brother’s was. The doctor leaned back on his chair and said, “There is nothing that can be done with your son’s condition.” I wanted to ask, “Would he be able to walk? Talk?” But before I could interrupt him, he continued, “He will need a lot of care.” I wanted to snap, yeah, I heard that already. Then he looked at me and said, “But life is precious. It is also resilient.” His voice was gentle and there was compassion in his pale, blue eyes. As we drove away from the hospital, down the streets of San Francisco, passing the concrete bulwarks of trade, industry and modernization, I realized that although the U.S. was one of the leaders in medical research, the knowledge about Arne’s condition was still unknown. Coming from the third world only four years ago, my hopeful spirit sank, and the stone of disappointment drowned my expectations. I felt no need to see another specialist after that. Or so, I thought.

Arne was about three years old when my family attended a camp meeting weekend where Dr. Ben Carson, the famous head of Johns Hopkins Pediatric Neurology was the keynote speaker. After his talk, I pushed Arne’s stroller through the crowd, and stopped him right in front of the exit door from the stage. “Dr. Carson, my son was diagnosed with delayed myelination,” I said, looking up at him. “Please, what can you say about that?” He bent and looked at Arne, then he turned to me, and said, “The myelin is a grayish substance that insulates the neurons of the brain. It’s also slippery and it serves as a transport system of signals between nerves.” Then he rubbed his two index fingers together and continued. “Imagine these are two live wires. If you remove their insulation and they rub against each other, sparks will happen. That’s the seizures. The myelin starts around the third trimester and it continues to develop after birth. Delayed means it didn’t develop as it should have.” He paused, perhaps to see if I understood. I nodded. I could see his explanation. “Nothing can be done to treat this condition,” he added. “But there are two things you can do. Don’t give up on him, and pray.” I inhaled deeply and said, “Thank you, doctor.” What he said gave me a tiny glimpse into my son’s intricate malfunctioning brain. I also felt that on top of his knowledge in neurology, this brain surgeon also knew what a mother’s heart is made of. I walked back towards our cabin, careful not to run the strollers’ wheels over the stones scattered on the ground.

Months passed. Arne did not crawl. He did not reach out, and his hands could not hold a toy. He was spoon-fed with fork-mashed food because he could not chew. He was not blind but he did not look. Arne did not talk. He yelled when he was hungry and when his diaper was soiled. He was not deaf because he could be awakened by noise. Sometimes he would stop yelling when I called out, “Arne, Mommy is here.” That gave me comfort. Arne “chewed” on his fingers —self stimulation — the occupational therapist explained. Elbow splints were used to prevent Arne from bending his arm to his mouth, but he found his way out of them anyway. His seizures did not go away and medication was often changed or modified. The physical therapy was stopped after noting “no progress”, and the wheelchair arrived. True to what the doctors said, Arne needed total care. I learned that resilience made care-giving constant and unfailing. But I also discovered that resilience is not self-supporting, for “it is about how you recharge, not how you endure.” I read that somewhere, and found it to be true.

I believe it was one of those days when my resilience tank was depleted, and seething with frustration and anger, I yanked Arne out of bed and “walked” him around the house. I was fixated with the idea that walking was the epitome of normalcy. My husband thought there was no point in it, but after a few months, Arne started bearing weight and making stepping motions supported by either one of us holding him from behind. I felt that our “walk therapy” was working, and my prayers were being answered. My tank was not always full, but it was neither empty.

One day, while teaching a piano student, the mother mentioned to me that she has a thirteen-year-old son with autism. She told me that the police had brought him home past midnight the other day, again. “No matter how we lock all the doors and windows, somehow, he manages to get out of the house when all of us are asleep,” she said, looking resigned and defeated. As I listened to her, a chill swept over me, for suddenly, I saw what was going to be Arne’s reality if he could walk —wandering everywhere, an easy prey to the human snakes, wolves, and tigers prowling on the streets. I cringed, for I knew in my heart that I would not have the resilience to deal with that. Right there, I closed my eyes, and said, “It’s ok, God. It’s ok if Arne does not walk.”

Five years after Arne was born, the movie “Lorenzo’s Oil” hit the theaters. Nick Nolte and Susan Sarandon played the part of Augusto and Michaela Odone, the parents whose son was afflicted with a rare neurological condition. The Myelin Project was launched and medical breakthroughs have emerged from myelin research ever since then. By that time, my interest in any findings about delayed myelination had waned. I already knew everything there was to know about Arne. As the doctors said—he will need a lot of care, and that nothing can be done to treat his condition. I was also advised not to give up on him, to pray, and that, no matter how it is manifested, life is precious and resilient.

On his ninth birthday, I wrote in my journal, “Nine years. No progress. A constant daily routine of feeding, toileting, etc. Why hasn’t there been any slight mental improvement? If only I could witness a miracle of interaction outside himself. Play, child. Play! Touch something! Look at something! Is there anything that would let me know what’s inside you?”

Arne functioned like a four-month old throughout his life. Unable to spread his wings, and totally dependent on the care of others, he was the ugly duckling that stayed on the ground. In 2021, after a sudden illness, Arne passed away. On that day, I imagined his spirit soaring swiftly towards the cloudless sky like a perfect, beautiful swan. He was thirty-four.