Kim’s Story: A Family Bond with ALSP

In 2019, my brother Jeffrey Cade was 42 when he awoke one morning unable to speak clearly. Jeffrey immediately called our family, and we urged him to drive to the hospital. After an overnight stay, the doctors assumed Jeffrey had a minor stroke and asked him to follow up with a neurologist. By the time Jeffrey met with a neurologist, he had begun having gait issues (difficulty walking). After a series of MRIs, spinal taps, and blood work, Jeffrey was misdiagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS), a diagnosis he would have for the next two years.

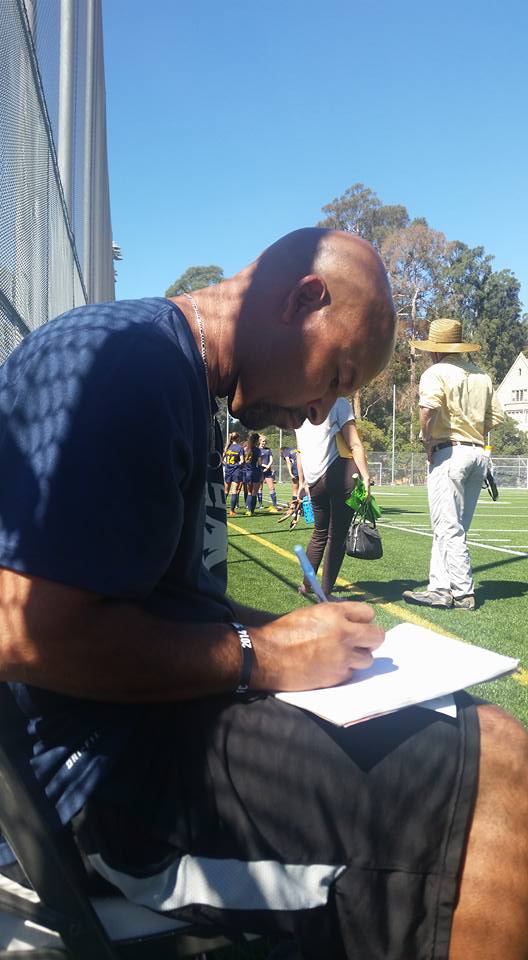

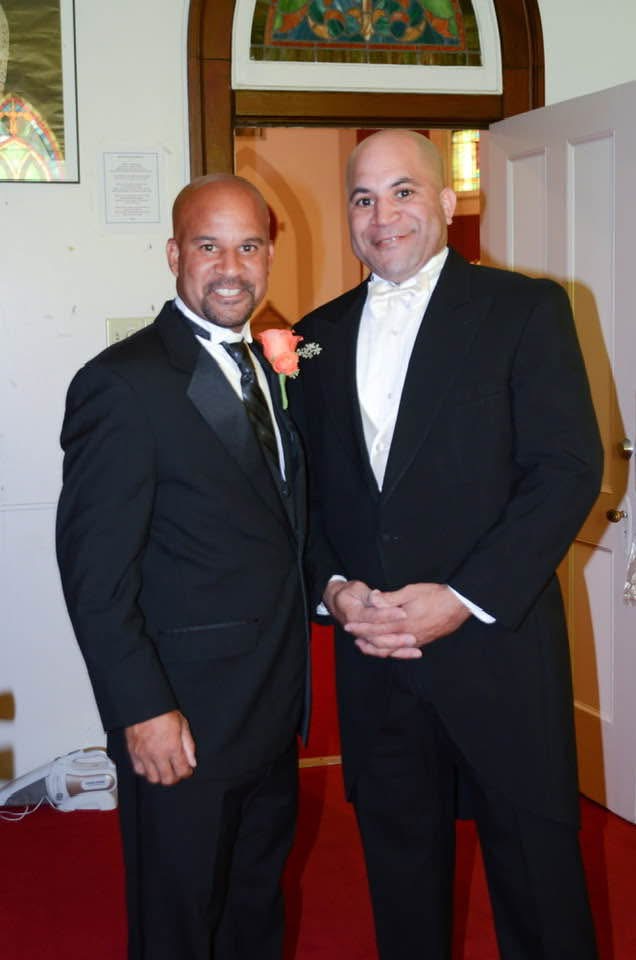

Jeffrey’s decline was swift. He was in a wheelchair by the fall of 2020, even while on infusions for MS. His speech still slurred, his hands increasingly weak, and he required 24/7 care that would be provided by our mom. Before Jeffrey’s diagnosis, he was a former semi-pro soccer player, launched a youth soccer organization, and coached for many years at the collegiate level. He was active, healthy, and in the prime of his life.

Jeffrey’s neurologist transferred to the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). There, another neurologist, Dr. Gelfand, observed Jeffrey. Unconvinced that Jeffrey had MS, Dr. Gelfand suggested a genetic test. A few weeks later, that test proved positive for a variant to the CSF1R gene. Jeffrey’s correct diagnosis was revealed as adult-onset leukoencephalopathy with axonal spheroids and pigmented glia (ALSP).

ALSP is a rare, rapidly progressive, and fatal neurological condition. Symptoms include difficulty with speech and movement as well as behavioral changes, often accompanied by issues like depression, anxiety, paranoia, and cognitive decline. Over time, ALSP results in a complete loss of speech and motor functions. The patient ultimately falls into a vegetative state before death. There are currently no cures or clinically approved treatments.

ALSP makes up about 10%-25% of all leukodystrophies. This disease also mimics other diseases like Parkinson’s, Epilepsy, MS, Dementia, and more. Overlapping symptoms are only one of the reasons why patients are constantly misdiagnosed, like Jeffrey. Additional factors include insufficient awareness and understanding of ALSP, as well as the absence of recommendations for genetic testing.

After Jeffrey was diagnosed with ALSP, a bone marrow transplant was suggested as a potential option, which could stop the progression of the disease, something not all patients with ALSP qualify for based on symptoms. While Jeffrey did qualify, our middle brother, Joseph, and I could not be donors after we tested positive for the same variant of the CSF1R gene. Still, in March of 2022, our cousin, Kai, became Jeffrey’s bone marrow transplant donor, and Jeffrey made it through the procedure successfully. Though he still requires 24/7 care, and our mom, at 80 years ol,d continues to be his Care Partner.

In the summer of that same year (2022), our brother Joseph began showing cognitive and behavioral symptoms at age 48. This former professional drummer, who wrote songs and lyrics with ease, displayed short-term memory gaps and was often confused. Joseph would get lost driving home from work, and while he was often referred to as “the life of the party,” Joseph began to withdraw from others. He was quiet, paranoid, and easily angered. Joseph and my sister-in-law, Kristy, visited with two neurologists who didn’t recognize anything abnormal in Joseph’s MRIs. However, after meeting with a neurologist familiar with ALSP, it was confirmed that Joseph had early-onset frontotemporal dementia (FTD) caused by the underlying disease, ALSP.

Joseph’s decline has been rapid. And unfortunately, he did not qualify for a bone marrow transplant due to his symptoms. Kristy, with the agreement of our family, made the difficult decision to place Joseph in assisted living in July of 2024. Joseph had two separate seizures and was at risk of being alone while Kristy continued working full-time, which was necessary for insurance and income. When a terminal disease like ALSP invades a patient’s life in their prime, financial resources and healthcare options are limited.

In May of 2025, Joseph lost the ability to communicate. As of September, he continues to decline, living the remaining of his life in hospice care with loved ones visiting regularly.

I remain asymptomatic and worry about when or if I will fall victim to ALSP. Still, I am proactive with MRIs every six months and participate in a natural history study while continuously raising awareness about ALSP and leukodystrophies as a whole.